Public Health Implications of Flat Funding

States Need Your Help

The current trend toward level or decreased Federal funding for state drinking water programs means that our ability to protect public health is at grave risk. Adequate Federal funding for the PWSS program (the principal funding source for states) is essential for us to implement the public health protection requirements of the Federal Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). States agreed to accept primary enforcement responsibility for Federal drinking water rules and regulations. In exchange, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) agreed to fund 80% of the implementation costs.

What is the PWSS Program?

State and territorial drinking water programs (except for Wyoming) are responsible for ensuring the approximately 150,000 public water systems across the U.S. protect public health and comply with National Primary Drinking Water Regulations. Funding for the states’ ability to fulfill this mission comes from four sources. The two primary sources are from EPA’s PWSS program and the set-asides from EPA’s Drinking Water State Revolving Loan Fund (DWSRF). The other two funding sources vary considerably from state to state and include funding from the state’s general fund and fees from water systems for plan review, inspections, etc.

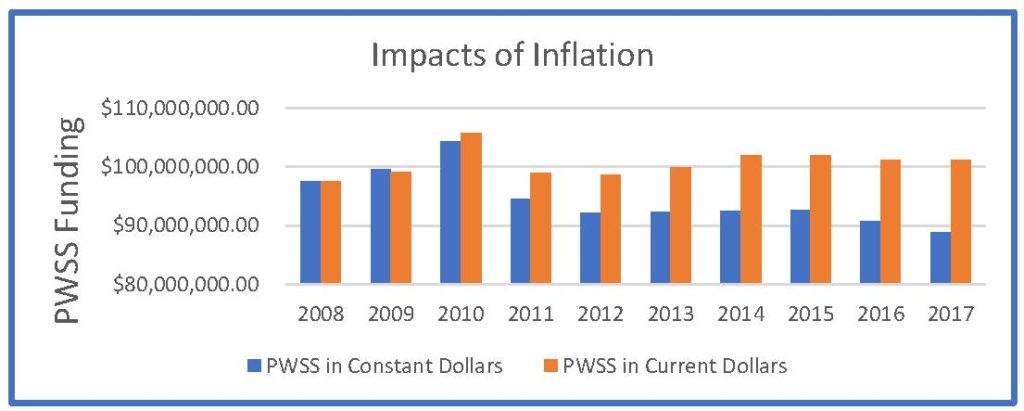

PWSS funding increased in the 1980s and 90s to reflect the increased regulatory workload for states and territories but has plateaued over the past 20 years. Since 2008, the PWSS appropriation has hovered around $100 million and has created a significant inflation gap as shown in the table below. In FY14, Congress funded the PWSS program at $101.9 million, an amount that has not increased since then. FY18 funding continues at the same level and FY19 is expected to reflect at the same level of funding, or possibly decrease.

Flat Funding for the PWSS Program Threatens Public Health

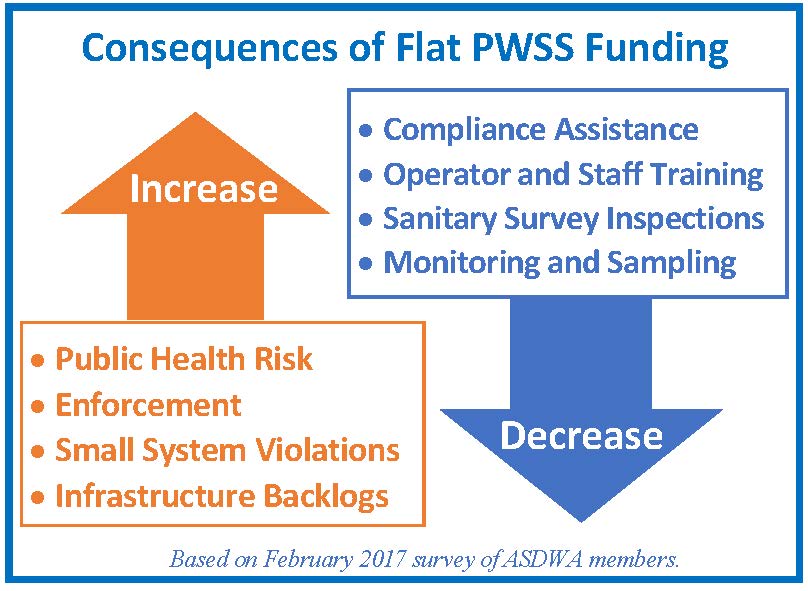

Despite flat funding for the PWSS program over the past 20 years, PWSS implementation costs for the states and territories have continued to rise. When the 1996 SDWA amendments were promulgated, state drinking water programs implemented public health protection regulations for 83 contaminants. Today, they implement regulations for more than 90 contaminants, and the newer regulations are considerably more complex and challenging to implement than prior regulations. At the same time, states realized the benefit of protecting public health more proactively and implemented these effective initiatives, such as source water assessments and protections; technical assistance with water treatment and distribution; and enhancement of overall water system performance capabilities.

Limiting or decreasing funds to an already very constrained state budget further constrains the ability of state administrators to fulfill our mission of protecting public health. This reduction forces administrators to make spending choices with considerable financial, legal, health and social risks, such as deferring infrastructure investments, cutting inspections or reducing water quality testing. The most critical of these risks is the one to public health. Put simply, decreasing these funds, or keeping them flat, puts the health of our citizens in jeopardy. Following are two state examples with links for more information.

- Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection sent a letter to EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt in March 2017 that outlined the potential impacts of substantial PWSS cuts on the citizens and businesses of Pennsylvania, including the statement, “…at least 30% fewer inspections for the Commonwealth’s 8,500 public water systems [would occur], hampering our ability to detect contaminants like lead, waterborne pathogens, and putting Pennsylvania’s 10.7 million water customers at risk.”

- Colorado: On August 10, 2017, the Water Quality Control Division in Colorado’s Department of Public Health and Environment posted a fact sheet describing staff and service level reductions should Federal funding decrease for the drinking water program.

Lead and Copper Rule Example: Consider also EPA’s recently proposed Long-Term Revisions to the Lead and Copper Rule (LT-LCR). In assessing EPA’s regulatory options, ASDWA conducted a Costs of States’ Transaction Study. The resulting data estimates that the costs of states’ staff time for the LT-LCR would be in the range of 72% to 95% of current PWSS funding. This effort to protect public health is clearly unachievable without additional Federal funding support.

A Funding Increase is Needed

The information here presents the very real and dire consequences that reduced funding for the PWSS would create. Continued flat funding for the PWSS program is not sustainable and we urge Congress to consider increasing PWSS funding, not keeping it flat or reducing it.

| FY 2013 | Available Resources (from all sources) |

Needed Resources (from all sources) |

Funding Gap |

| Minimum Base Program | $385 million | $625 million | $240 million |

| Comprehensive Program | $440 million | $748 million | $308 million |

This table represents the estimated FY 2013 funding gap from the ASDWA Report, Insufficient Resources for State Drinking Water Programs Threaten Public Health, where a comprehensive program includes additional activities undertaken by states to achieve the public health protection vision and goals established by the SDWA. Funding for the PWSS program should be double – ramped up over a period of five to ten years to allow states and water systems to achieve the public health goals envisioned by the SDWA.